Sawtooth Printhouse Pays Tribute to the Old and Slow

Sawtooth Printhouse Pays Tribute to the Old and Slow

by Shana Watkins, Nashville

Many moderns, especially very youthful ones, would give up typesetting after the first time they printed a mistake. To labor over the many tedious steps involved in effectively operating a printing press (selecting just the right type, taking an hour or more to arrange the letters and design, inking the printing press evenly, loading it with the appropriate paper, and cranking the press for each copy) only to find that one’s finished product is riddled with misspellings and/or punctuation errors would send most of us into an emotional tailspin because it would mean starting almost completely over.

But a good printer will, as printing press extraordinaire Nieves Uhl puts it, “use all of [her] skills and reasoning to check [her] settings, type, and the ink repeatedly during the printing process.” It is a slow process, but one that Uhl finds remarkably rewarding. In fact, the time one must devote to using a printing press is what makes the process fulfilling, Uhl testifies. Uhl recognizes that the time she must devote to the process makes her a more detail-oriented person and, therefore, a better artist. She is deft at observing things someone in a hurry will miss.

Nieves Uhl, along with her business partner, artist Chris Cheney, founded Sawtooth Printhouse last fall. They set out to not just create a “slow” business that celebrates creative, manual manufacturing as opposed to mass production, but also to create an inspired space in which no matter where one turns, one is reminded of a time antecedent of computers and the lightning fast lifestyle high technology gave way to in the 1980’s, a decade after computer technology began to make printing presses obsolete. Cheney, a talented handyman in his own right, set out to refurbish the somewhat dilapidated garage outbuilding of his home in art-friendly East Nashville, Tennessee, to use it as a space that would inspire his and Uhl’s printing ambitions.

How better to fuel the inspiration behind an antiquated art form than to use primarily reclaimed or repurposed materials for the space? The back wall of the space is a fascinating dark curtain of 150-year old poplar planks salvaged from a smokehouse. Cheney claimed the two side windows from one supplier’s accidental surplus order and the double-insulated glass of the front and rear windows were donated to Sawtooth by a prominent Nashville artist who was making some changes to his own studio. The two spacious tables central to the space were once one large table Cheney already owned. The partners rescue scraps of wood that become their design blocks. In the interest of being as off-the-grid as possible, Cheney even entertained the idea of installing a wood-burning stove in the space, but his insurance would have completely dropped his coverage if he had done so!

Even the paint on the floor of the shop was salvaged from some other improvement job. At this, Uhl chuckles, "Maybe we're just cheap!" but agrees that their thriftiness forces them to be resourceful and innovative.

Perhaps the most fascinating story Uhl shares about the shop is the tale of how she acquired one of the two enormous type cabinets. A woman from Fairview, Tennessee contacted Hatch Show Print, where Uhl was cutting her printing teeth at the time (Hatch Show Print is the famed print shop that could arguably be described as one of Nashville’s finest crown jewels), to inquire if anyone there might be interested in taking a type cabinet that had belonged to her father off her hands. The cabinet - probably a relic from the 1940s - had been damaged and its contents completely disorganized during a tornado and was sitting almost in ruins, typeface completely scattered in the woman's garage and yard. Uhl and her husband, Jeremy, immediately set out to investigate. What they found was a treasure they brought home to sit in their own garage for nearly four years before the space Cheney created made it possible for the majestic cabinet and its type to once again be used and loved.

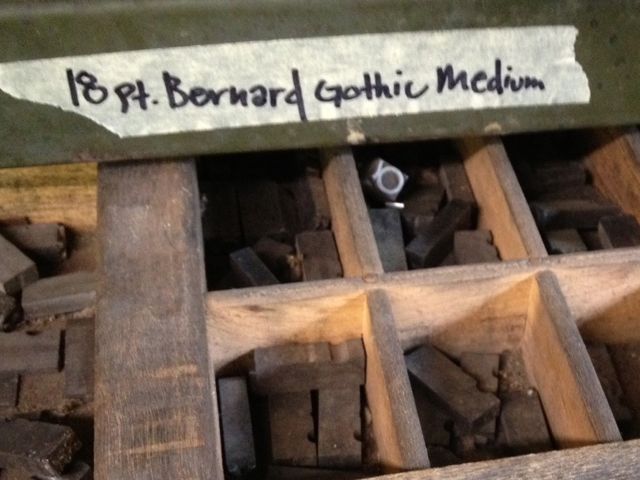

The salvaged Fairview cabinet, with its now barely noticeable bent frame (thanks to Tennessee’s infamously extreme weather which tried with all its might to wrap the behemoth around a tree trunk), fresh coat of paint that cured its cancerous rust, and masking tape that thoughtfully marks each of its drawers of typeface (i.e. “18 pt Bernard Gothic Medium”) has never been happier than it is now in its new home.

And then there’s the drawer marked “Mystery Type”. Unfortunately, a typeset is only of value if it is alphabetically complete. “No one wants to spend up to two hours putting together a whole poster or wedding announcement only to find that you’re missing the letter J,” explains Uhl. But unwilling to part with any homeless letter they come across, Uhl and Cheney toss hapless letters into the “Mystery Type” drawer. Uhl laments, “Who knows how many letters are still buried in the dirt in Fairview?”

The two artists are also unwilling to part with the remnants left behind by the two known previous inhabitants of the outbuilding who are yet posthumously adding character to the space: the previous homeowner, and his predecessor, a seemingly colorful character named Gaylord. Gaylord, who had outfitted the building with gobs of fishing paraphernalia, left behind a collection of Polaroid snapshots of himself holding his aquatic trophies. The previous owner of Cheney's house and garage - a man who used the space to refurbish and reupholster Volkswagen automobiles - held onto those photographs just as Cheney does now. Cheney also can’t quite let go of the random items such as a package of Black Cat Firecrackers and a very old tin capsule of fuses. He keeps these mementos in a box below one of the shop’s worktables, though he can’t say why.

But it must be because of Cheney’s and Uhl’s appreciation for the slow pace of bygone days; those artifacts that probably belonged to old Gaylord remind their handlers of a time when a printing press was high technology, and each project carefully worked upon it a labor of love. Uhl speaks passionately about her love for the slow, thoughtful process that, she believes, encourages her to be a better artist. “It takes a better designer to design by hand that frantically at a computer. There is something therapeutic about turning each letter over in your hands and even thinking about the person who made that individual letter.”

“High schools used to offer typesetting classes,” explains Uhl, “Now they just do everything on a computer. Computers are great, but the very fast lifestyle they’ve [birthed] goes too quickly for the human brain to pause and process. So, we miss things - things that you're only going to discover within a process.” She picks up a chunky rectangular block of dark metal and says, "This is my tab key!"

Even the logo Uhl and Cheney chose is a send up to the beauty of manual synergy - a two-person crosssaw like the one that hangs above the door of the little shop.

Sawtooth Printhouse operates almost entirely off the grid. Sure, they have electricity for their lights, box fan, and space heater, but Uhl points out that when it comes to her art, “I have to be the machine! No electricity necessary. This press is nothing without me, and I cannot achieve what I want without it.” A press doesn’t think for its operator the way we think of a computer doing; indeed, to even be necessary, a press is completely dependent upon a person.

Sawtooth Printhouse in located in Nashville, Tennessee. They are equipped and ready to complete jobs such as designing and printing custom wedding invitations, birth announcements, event posters, etc. Find them on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/SawtoothPrinthouse, or view their website sawtoothprinthouse.com.